Part 4 – Six Elements of Project Controls –

Competency and Level of Effort

By Lance Stephenson, CCP FAACE

Lance Stephenson, CCP FAACE, is a contributing member of AACE’s Technical Board and is a Certified Cost Professional. Lance has provided direction in the areas of organizational design, process improvements, auditing, maturity assessments, and the development and implementation for improved capital portfolio and project effectiveness. He is a senior leader and manager with over 35 years of experience in the operational, capital portfolio, and project delivery environment and is currently the Director of Operations for AECOM.

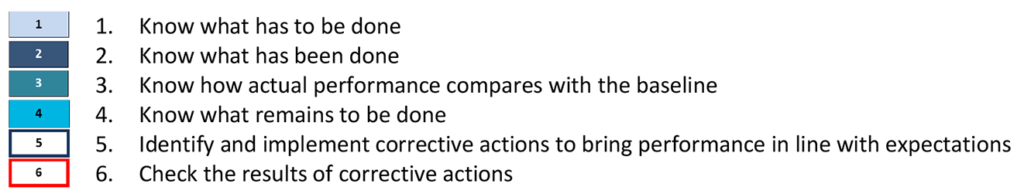

This article is the fourth in the series on the Six Elements of Project Controls. Past articles included the basics of the six elements of project controls, the effect of quality, and the maturity required. Today’s article discusses the competency and level of effort required to manage these elements of project controls. As discussed in the earlier articles, the six elements of project controls are considered the operational steps for managing the functional project controls requirements within a project. The six elements include the following:

It is not enough for a project organization to just know about these elements, their expected quality, and maturity requirements to make their project successful. Two other ingredients to apply for success are competency and level of effort. Competency is the possession of sufficient knowledge or skill, while the level of effort is the amount of work needed to execute the project’s activities. For an organization, competencies are core masteries that define what, who, and how the organization will deploy its employees to accomplish its overall goals. The level of effort defines the intensity (scale) and when deliverables need to be completed. Based on these expectations, the organization and its employees must provide the necessary competency and effort to complete the defined work.

Before developing competency models for enhanced project delivery, the organization must recognize its core strengths and understand the requirements needed to succeed in its business endeavors. This includes understanding the complexities and risks associated with the projects they deliver. While most executives focus on the final installed costs to determine if the project should be executed, other factors should be considered. For instance, is the organization experienced in designing or constructing the project (i.e., qualified resources)? Does the organization have the understanding and ability to perform different project delivery strategies (design-bid-build, design-build, etc.) and contract types (time and material, firm price, etc.)? Is the project introducing any new technology the organization has not executed before? Is the delivery of the project urgent and a priority? Is the project critical (and vital) for the organization to meet its business objectives? Does the project need to be delivered in a compressed time frame? Are there major contractor interfaces and logistical coordination requirements? Finally, are there any significant uncertainties and constraints?

Understanding these factors allows the organization to determine the required competencies and scale its operations accordingly. For more complex and riskier projects, you will require advanced technical skills, knowledge, and experience to administer the project to a favorable outcome. For projects with minimal complexity and risks, the organization may choose to reduce its oversight (administration) and surveillance (observation).

For owner organizations, it has been identified that approximately 1 to 3 percent of the TIC costs of the project are dedicated toward the project control efforts. Projects with more complexity and significant risks may require more experience and oversight (3%), while simple projects may require less (1%). Please note that while the top-down estimating approach provides the basis for determining budgets and resources, the project team should support the development of the Class 3 estimate with a bottom-up, deliverable-based estimate as defined by the project controls scope of work and requirements.

Competency

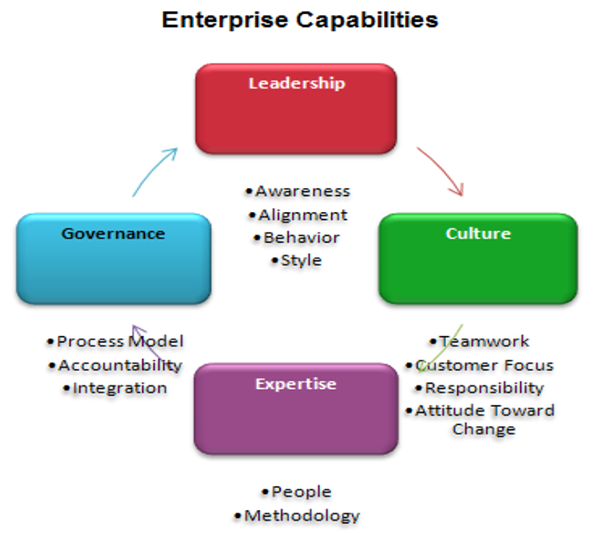

Once the organization has defined the type of project work that it wants to engage in, as a first step, it can now define the desired enterprise capabilities, as illustrated in Figure 1. This diagram itemizes the primary elements required to support the implementation of the overall competency models for management, which further supports their employees and their development. Without these attributes, introducing practical competencies will be challenging.

Figure 1 – Enterprise Capabilities

Organizational Competency:

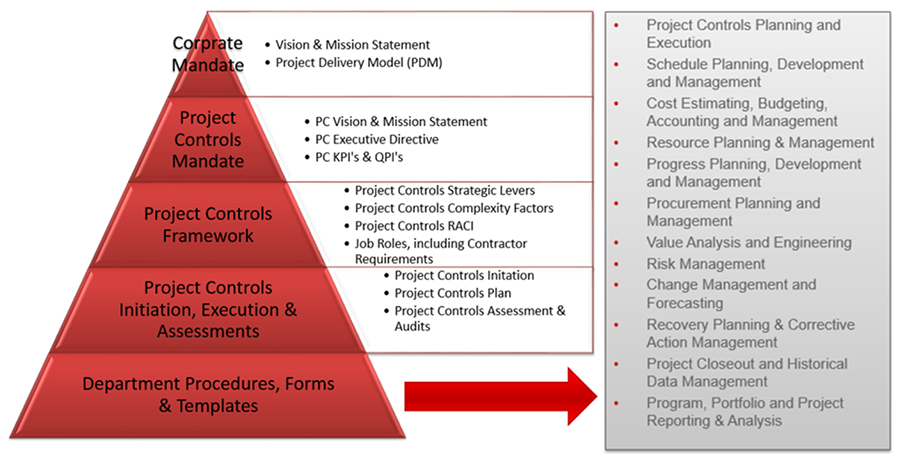

With the enterprise capabilities defined, the organization can begin establishing the taxonomy of the organizational competency. When defining organizational competency, it must identify the corporate and functional project mandates that support the overall business strategy. The organization should also define its vision and mission statements, executive directives, and key performance indicators (KPI). Subsequently, the organization must establish its required project management and project controls standard practices, processes, templates, and tools to provide the appropriate monitoring levels, controls, and project reporting. These standard practices must be functionally adequate and assessed against approved standards, preferably best practices known to produce favorable outcomes. Figure 2 provides an example of the hierarchy of deliverables that define and support organizational competency. The introduction and adherence to this hierarchy will provide the appropriate level of awareness of the health of the project and organization.

When establishing the business norms for operating a project delivery model, the organization will be required to provide the appropriate context and governance for applying any policies, procedures, and processes. An organization cannot be successful if it does not ensure compliance with these requirements. The policies, procedures, and processes are written to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the organization, as well as improve the timeliness of decision-making and problem-solving. Finally, by ensuring compliance, the organization can identify and mitigate enterprise, portfolio, and project risks. Policies, procedures, and processes are written to protect the organization’s interests, not to obstruct the membership of the organization nor the delivery of the project. Organizations may want to reference AACE’s Total Cost Management Framework and associated recommended practices to develop organizational competencies.

Employee Competency:

Another failing aspect of some organizations is the lack of defined roles, responsibilities, and expectations. This, in turn, affects the required competencies of the organization’s employees. If they do not know what to do, don’t expect them to do it. Worse yet, expect them to do the wrong thing. The organization must define clear and concise competencies for each of its roles within the project controls environment. These competencies should be observable abilities, skills, and knowledge of specific areas of the project controls domain. This also includes the motivations, traits, and behaviors needed to perform the job successfully. For the organization to further develop the competencies of its employees, a competency development program should be introduced. Organizations will need to consider the following:

- The scope of work for each core service or targeted area is based on the pre-defined organization competencies.

- Identify the needs for each specific discipline within the category, including:

- Level of effort for each discipline (risk vs. reward).

- Interfaces between disciplines and coordination activities (integration).

- Define the level of skill required for each assigned task and assign the appropriate skill category.

- Assign entry-level staff to less technical tasks.

- Assign a more experienced resource mix for highly technical /risky /complex scopes of work.

- Once these items have been defined, determine the gaps where enhancements can be introduced.

- Introduce appropriate training seminars/events.

- Promote team members to participate in practice groups or academic societies that improve competencies.

- Introduce train-the-trainer as well as mentorship programs.

- Introduce an apprenticeship program that advances staff through organized education.

- If staff is unavailable, the organization will need to partner (contract) with a 3rd party organization to provide the required services.

Another suggestion for employees to improve their competencies is to achieve professional certifications from reputable organizations. These certifications promote a level of professionalism, expertise, and credibility. The following list identifies specific industry-relevant certifications education institutions offer within the project delivery domain.

- Certified Cost Professional (CCP) – AACE International

- Planning Scheduling Professional (PSP) – AACE International

- Earned Value Professional (EVP) – AACE International

- Certified Estimating Professional (CEP) – AACE International

- Decision and Risk Management Professional (DRMP) – AACE International

- Project Risk Management Professional (PRMP) – AACE International

- Certified Forensic Claims Consultant (CFCC) – AACE International

- Certified Supply Chain Professional (CSCP) – The Association for Supply Chain Management or Supply Chain Management Professional (SCMP) – Supply Chain Canada

- Certified Value Specialist (CVS) – SAVE International

- Project Management Professional (PMP) – Project Management Institute

For a project team member to be effective in their role, the organization needs to ensure these individuals have the capability and availability (for the role’s complexity), aptitude, skills and knowledge, and commitment to, and value of, the work required of this role. Organizations may want to introduce scalability (levels) to their defined roles, i.e., junior, intermediate, senior scheduler, estimator, etc. Organizations may also want to reference AACE’s recommended practice, RP 11R-88, Required Skills and Knowledge of Cost Engineering. AACE offers other skills and knowledge RPs for other functions under the cost engineering domain.

Level of Effort Based on Assigned Deliverables and Phase Gates:

As discussed earlier, knowing the required level of effort and when an organization is required to unleash these competencies is equally important. No one wants to attend the dance late (or even too early). To methodically complete the execution of deliverables, organizations should introduce a phase-gate process. This approach promotes the timely release of required documents so that information is available to support effective problem-solving, decision-making, approval(s), and advancement.

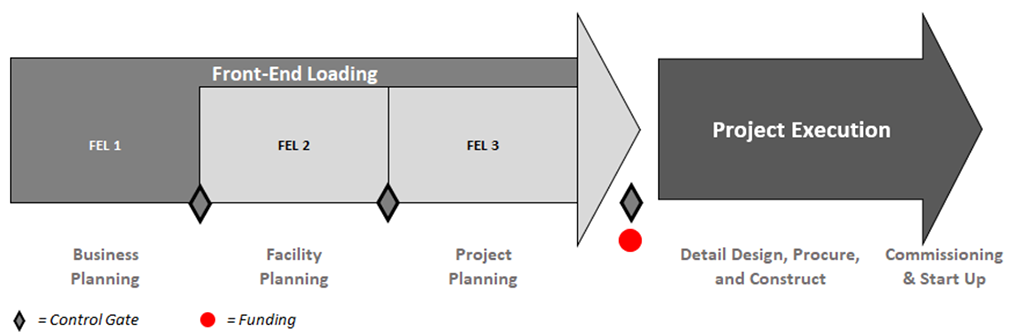

A phase-gate process is a project life cycle technique in which an initiative or project (e.g., new product development, software development, process improvement, business change) is divided into distinct phases or stages, separated by assessment and decision points (control gates). For some users, especially owner companies, the phase-gating process is considered a go, no-go decision-making model where the continuation of the project is decided by managers, steering committees, or governance boards (at each control gate). It also enforces that the project teams will apply the required quality when developing the deliverables as well as ensure the maturing of the scope of work as it passes through the gates (deliverables are assigned to each phase, which are either completed in the phase or are further developed as the project moves through the phases). Figure 3 illustrates the typical phase gate for the process industry that an owner company may use. In this example, the phase gate is separated into two sections: front-end loading (FEL) and execution. Conceptual and semi-detailed engineering occurs during the FEL phases. Once FEL is complete, the project team usually receives full funding to move the project forward. Once funding has been approved, execution of the project occurs, where detailed design (engineering), procurement, and construction activities ensue.

Figure 3 – Typical Phase Gating Arrow – Process Industry

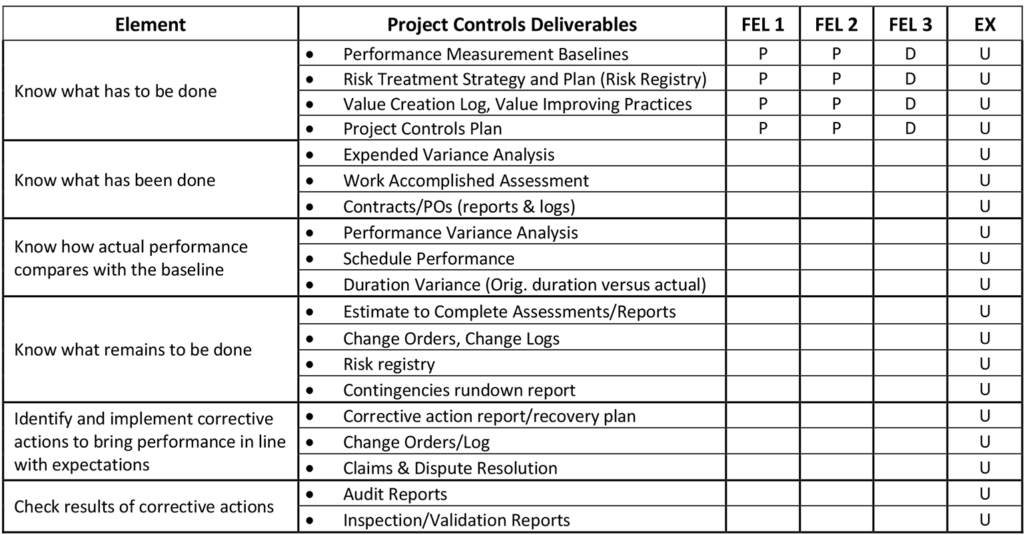

As stated earlier, project controls deliverables are assigned to each phase to ensure that the expectations are being met when required, as illustrated in Table 1. The table identifies the element in which the deliverable is assigned and the required maturity (level of completeness) of the deliverable (preliminary (P), detailed (D), or updated (U)). For a comprehensive list of project controls deliverables, please reference AACE’s RP 60R-10, Developing the Project Controls Plan.

Table 1 – Phase Gate Assignment of the Deliverables for the Six Elements of Project Controls

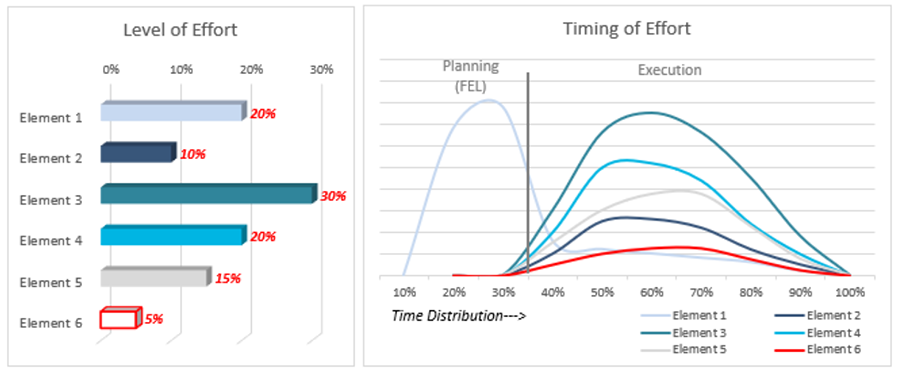

Completing the work during the designated timeframe is crucial to project success and ensures that the desired competencies and expectations are met without redundancy, overlap, or gaps. This also promotes healthy behaviors in developing and managing project expectations. If completed appropriately, the project team can then understand the level and distribution of these efforts, as illustrated in Figure 4. This further allows project teams to plan resources accordingly and properly administer the work to be completed.

Figure 4 – Level of Effort and Distribution – Proposed State

Figure 4 illustrates the level of effort. Element 1, knowing what has to be done, consumes approximately 20% of the total project and controls overall effort. Element 2, knowing what has been done, consumes approximately 10%, etc. The timing of effort graph illustrates the distribution of the effort for each element over the project life cycle. As illustrated, most of Element 1’s efforts (15% of the 20%) are concentrated in the planning (FEL) phase, while the remaining efforts for Element 1 (5% of the 20%) are being performed during the execution phase. This portion of effort for Element 1 allows the project controls team to update and re-plan (if necessary) the project based on the performance of delivery, changes to the project, the re-assessment of risks, and forecasting the final outcome. The remaining elements (2 through 6) are performed entirely during the execution phase. The level of effort and distribution over time allows organizations to estimate the costs of the project controls team.

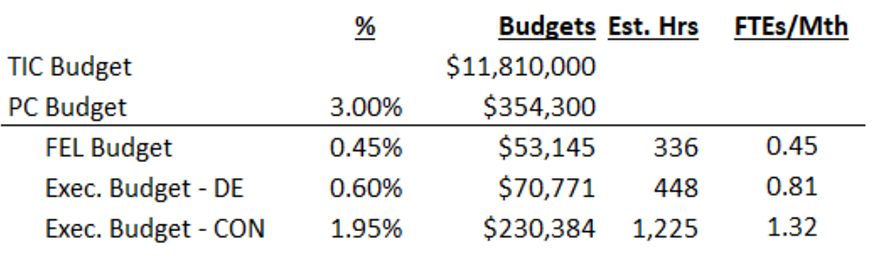

To demonstrate the calculation for determining the costs of the project controls efforts, the following example is provided. A company was required to install an interconnecting piping system to an existing facility. The total installed cost (TIC) of the project was estimated at $11.810 MM. This new interconnect piping system would allow a different feedstock to be introduced into the facility. The FEL phases would take four months to execute, while the detailed engineering and construction period was expected to take eight months. For this project, it was determined that it was highly complex and had significant risks, and therefore, it was identified that 3 percent of the TIC costs should be dedicated towards the project controls efforts. With this said, the project controls budget was set at $354,300, of which 15% ($53,145) was allocated to manage the FEL phases. The remaining funds of $301,155 were used to manage the execution portion of the project (home office engineering and field construction). Table 2 illustrates the budget components of the project, the percentage of TIC, estimated hours, and full-time equivalents (FTEs) of required personnel. The organization now has a budget that supports the required competency and level of effort at which to perform the project controls duties.

Table 2 – Project Controls Budget for the Interconnect Piping System Project

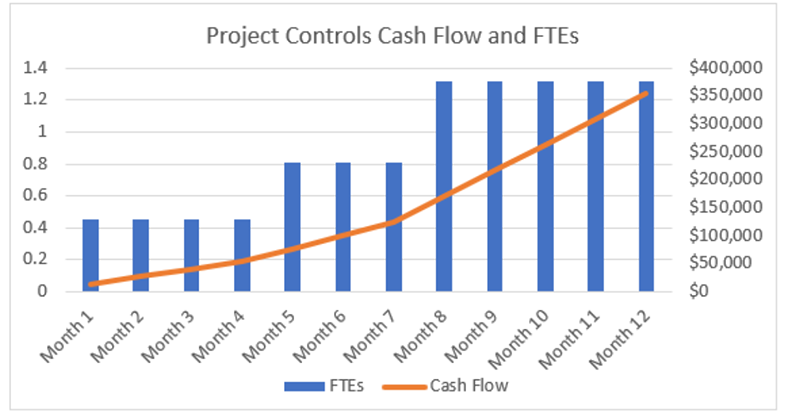

Figure 5 illustrates the cash flow projection for project controls for the example project. It displays both the cash flow and FTE requirements for the project life cycle.

Figure 5 – Project Controls Cash Flow

Going through the motions and simulating project controls efforts will only create negativity and minimize the functionality and value this profession brings to project delivery. Compound this issue with ill timing, and the results could be disastrous. Therefore, applying the correct competencies for the organization and its employees is essential. The success of using these competencies is also predicated on the level of effort and the timing of these efforts. The Six Elements of Project Controls, complemented with these competencies, further provide the organization with an objective approach to ensure project success.

Rate this post

Click on a star to rate it!

Average rating 4.8 / 5. Vote count: 8

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.