Improving Project Gatekeeping Through Stakeholder Alignment and Behavioral Decision Making

David C. Wolfson

Abstract–When looking at why many major projects fail to meet their cost and schedule expectations, the root cause is often a misalignment between the engineered solution and the owner’s business case. This article will explore this issue by briefly describing the gatekeeping process. At its core, gatekeeping is a decision-making process. The article looks at decision making in the context of projects. Stakeholder management, salience and interaction with gatekeepers are also explored. The interrelationships between gatekeeping, decision making, and stakeholder management is illustrated by looking at both a simple and a slightly more complex project. Even in these simple examples it is apparent how misalignment can occur. From an owner’s perspective, misalignment at the project approval stage can have very significant financial repercussions. This article offers three strategies to mitigate potential misalignment, based on the author’s examination of decision making and stakeholder management. This article was first presented at the 2021 AACE International Conference and Expo as OWN.3666.

Introduction

When looking at why many major projects fail to meet their cost and schedule expectations, the root cause is often a misalignment between the engineered solution and the owner’s business case. The owner’s gatekeeping function sets the parameters that various aspects of the business are evaluated against. This in turn defines the planning deliverables required at each gate, especially for the project execution team. When this effort breaks down, ill-defined and ill-prepared projects make their way through the process resulting in late changes and poor project results. This article shows that by understanding stakeholders, gatekeepers, and the decision-making processes, this misalignment can be mitigated.

The article will explore this issue by first describing the gatekeeping process. At its core, gatekeeping is a decision-making process. The article will look at decision-making in the context of projects. Key aspects of stakeholder management will be summarized. The interrelationships between gatekeeping, decision making, and stakeholder management will be illustrated by looking at two different projects as case studies. Finally, aspects of alignment and misalignment will be explored.

Gatekeeping

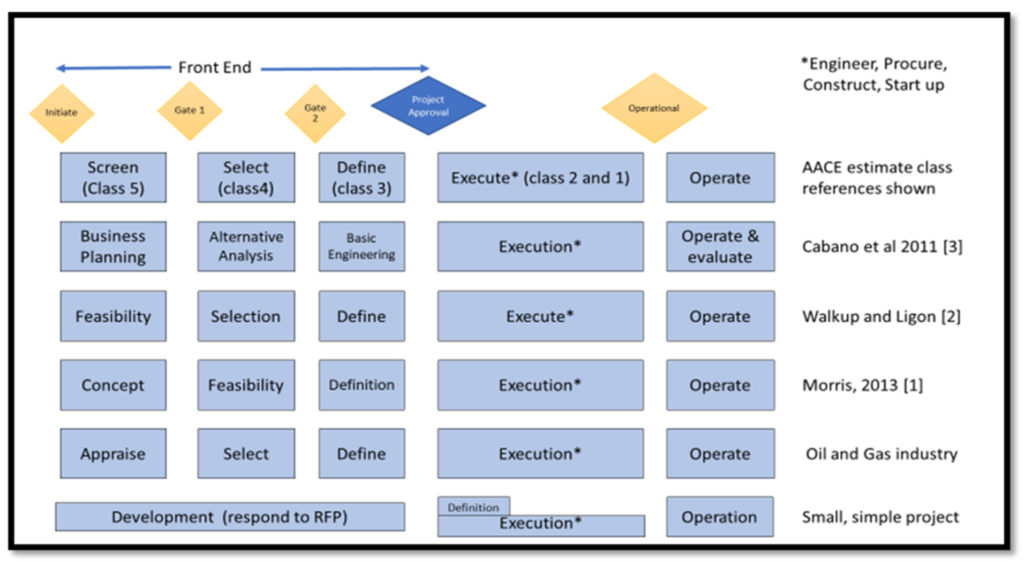

Best practice in capital project execution is based on a stage gate approach. For asset creating projects, most organizations use stages and gates as shown in Figure 1.

Typical Stage Gates for Asset Creating Projects

Figure 1–Typical Stage Gates for Asset Creating Projects

Fundamentally, gatekeeping is a quality process. Its purpose is to ensure the project team is doing the right work at the right time. And it ensures that the work in the previous phase is done with the correct quality. For example, during the definitive estimate phase, most organizations have clear criteria to judge the estimate quality, including piping and instrumentation diagrams (P&ID) quality, level of quotations received, amount of work done exploring local labor rates and technology and risk assessments. Gatekeeping is essential to project governance.

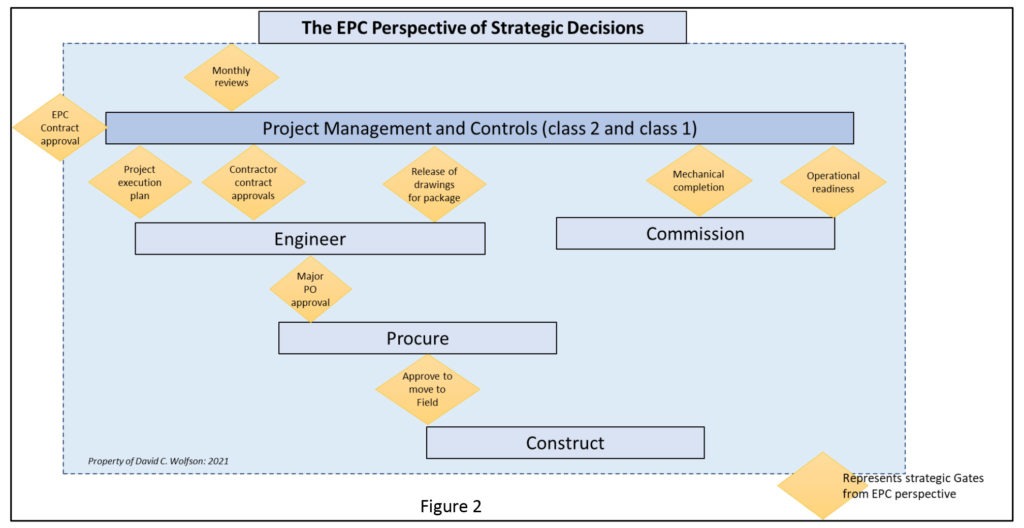

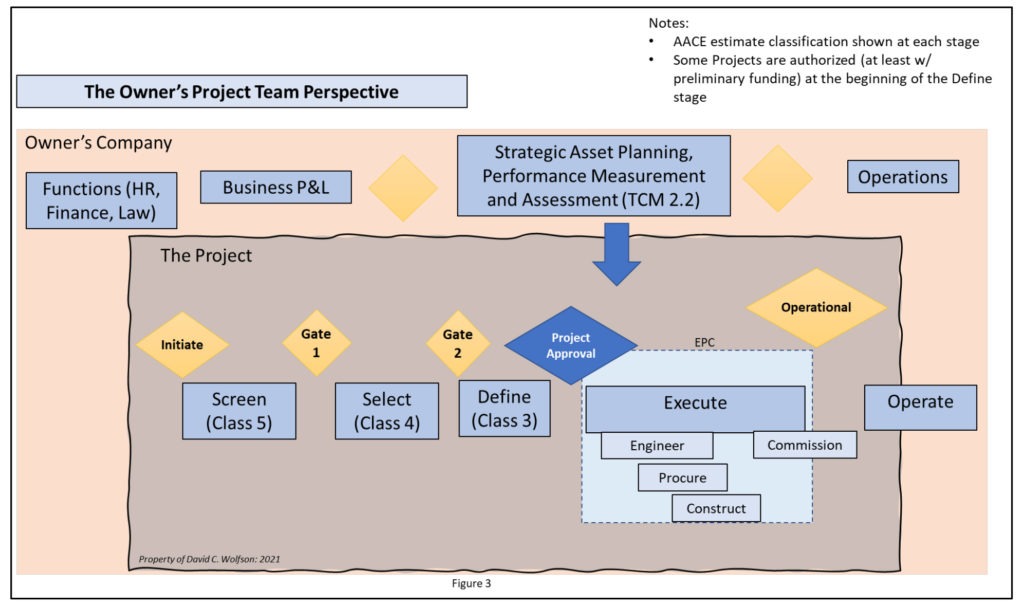

The purpose of the gatekeeping of course is to make a decision. Decisions can be thought of as either strategic, tactical, or operational (or even transactional). The characterization is a matter of perspective. For example, the decision to release a certain drawing for construction might be viewed as an operational decision by the owner, but strategic to the engineering contractor on a fixed price contract. Which bucket a decision falls into is less important than understanding that the perspective changes depending on if the decision maker is an owner, a contractor, or a subcontractor.

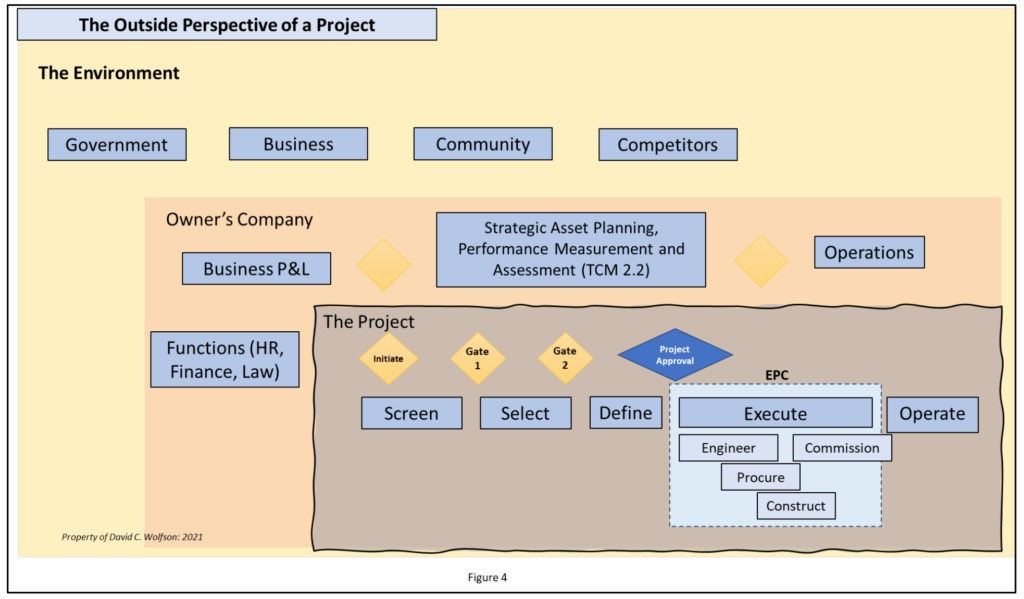

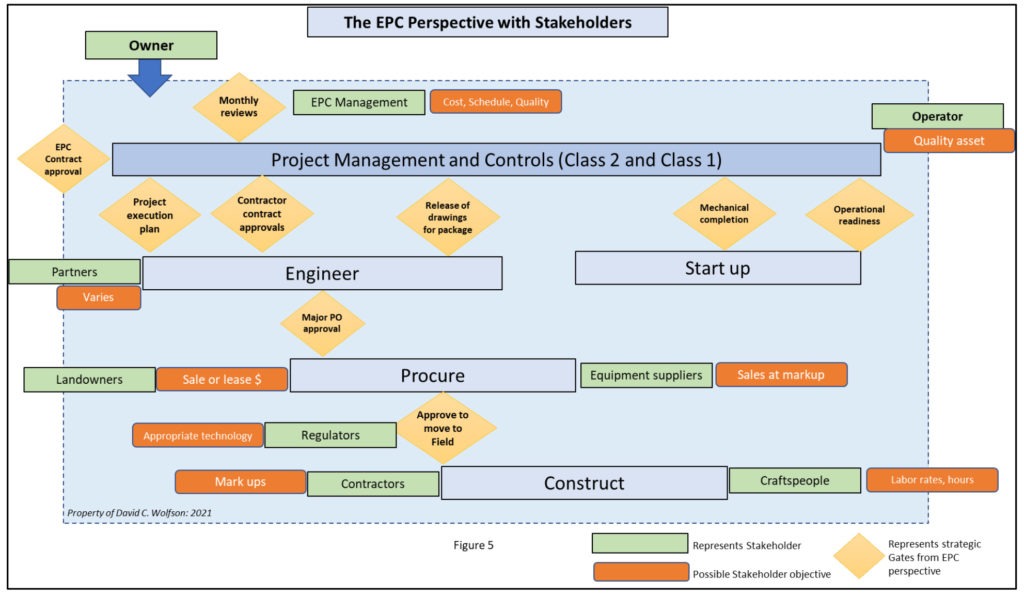

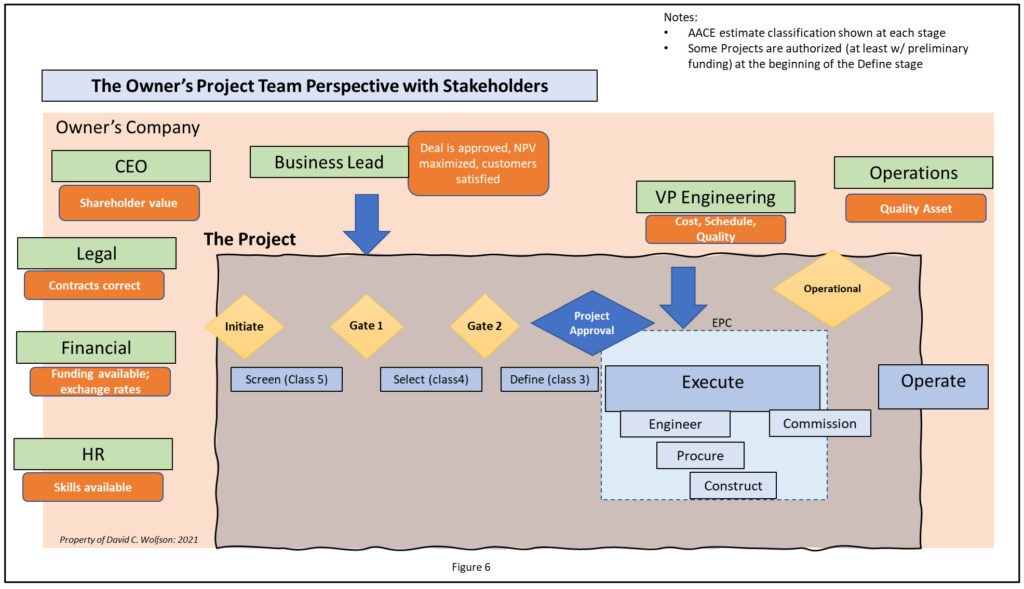

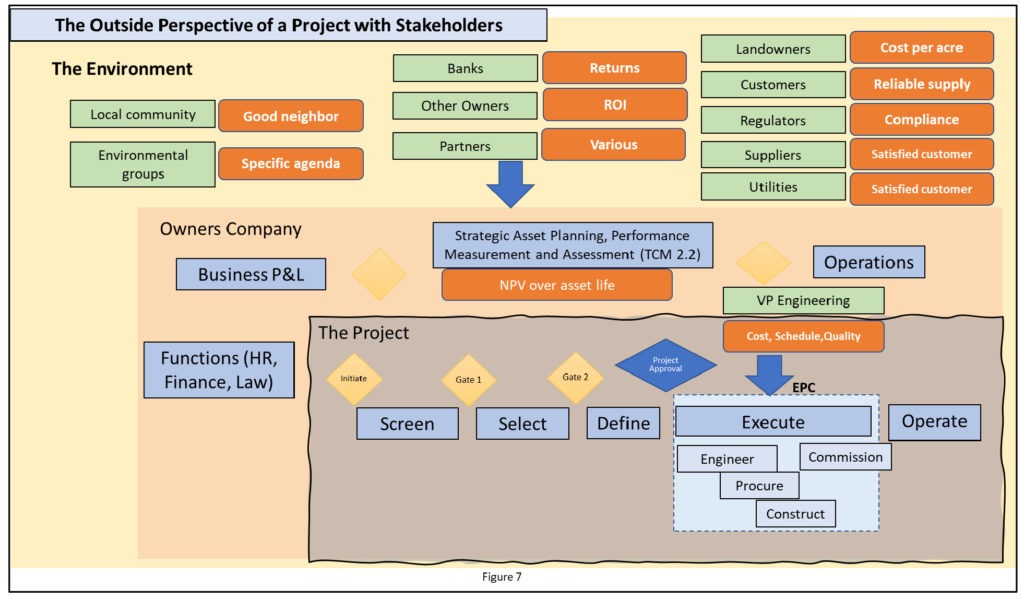

From an owner’s perspective, strategic decisions can be thought of as stage gate decisions. For example, project approval and final acceptance are strategic decisions. Figures 2 – 4 show the various perspectives of the EPC company, the owner’s project team, and the owner. Figures 5 – 7 add in the shareholders and their notional motivations. These figures represent some examples and are not meant to be hard and fast dogma. The purpose is to show that different perspectives have different decisions, different gatekeepers, and different stakeholders. Figure 7 shows the owner’s company perspective. External stakeholders include banks that are looking for sound financial returns, the local community that is looking for a good neighbor (low noise, good employer, environmental steward) and regulators that are looking for compliance. How to manage these stakeholders will be discussed later.

Figure 2–The EPC Perspective of Strategic Decisions

Figure 3–The Owner’s Project Team Perspective

Figure 4–The Outside Perspective of a Project

Figure 5–The EPC Perspective with Stakeholders

Figure 6–The Owner’s Project Team Perspective with Stakeholders

Figure 7–The Outside Perspective of a Project with Stakeholders

Decision Making

Essentially projects are a series of decisions and gatekeeping is an example of a strategic decision from the owner’s point of view. From an owner’s project team’s perspective, the following decisions can be thought of as either strategic, tactical, or operational:

- Strategic: Decision to fund development (initiate), decision to fund definitive estimate (gate 2), project authorization, technology decisions, decision to commit funds (long lead procurement items, easements for pipelines, environmental permitting modeling) when project or money is at risk, high level execution strategy/risk assignment (partnering, EPC role, self-execution, degree of oversight), permit strategy decisions, decision to take over operation.

- Tactical: Execution strategy fundamentals (outsourcing decisions), schedule milestones, procurement packaging strategy, major equipment specification and T&C requirements, modular strategies, design basis/design margins to be used, foundation design strategies (large mats or many individual foundations, piling type to be used) controls philosophy, drawing detail approach (home run I&E package vs routing details), above ground vs below grade decisions, sub-contractor risks allocations, field staff strategies. These might be considered strategic by an EPC contractor.

- Operational: Specification inclusions, drawing package decisions (ex: structural steel details to be shown, drawing approvals and comments), decisions to add field staff as necessary, decisions to source inspect and/or expedite equipment, decisions to accept vendor deliveries in the field and/or hold suppliers accountable for changes, decisions to make up work with increased crews vs more hours (4 x 10’s vs added Saturday make up days). These might be considered tactical or strategic by an engineering or construction contractor.

The AACE International Total Cost Management Framework lists an objective approach to decision policy and investment decision making including planning for decision making, determining deterministic decision models, and evaluating alternatives prior to an approval decision. [4]

Engineers are trained to think rationally. Much of the project management and cost engineering literature assumes both project teams and gatekeepers are thinking rationally. For example, if construction is not fully complete, the assumption is that the gatekeeper will deny the project from moving into the startup state gate. Things are never quite so black and white of course. Typical questions that need to be clarified include how many punch list items are acceptable to be considered complete, can the plant be [HQ1] turned over system by system or area by area (i.e., have multiple gates), are utilities available and should that be considered, what level of equipment spares, or temporary piping are needed on site before turnover is acceptable.

At the project approval decision gate, a project approval might be assured if all requirements are completed per company requirements. For example, execution risks have been developed and quantified, financial analysis with sensitivities have been run, financing is secured and contracts or letters of intents on key operating assumptions have been legally reviewed. Yet the decision makers need to understand the basis and assumptions made for each of these inputs as each have built in biases. Probing questions might reveal, for example that the project contingency or scope completeness score was modified after some pressure was exerted on the engineering team. Gatekeepers want to believe the numbers brought before them as they provide a rationale for yes/no decisions.

Yet beyond definitional issues such as those listed above, is the realm of non-rational thinking. Gatekeepers and project team members have biases and motivations that are impossible to strip away. So, it’s important to understand some behavioral elements of decision making.

Broadly speaking there are three ways of understanding decision making in projects. This article will only focus on two. [5] The first, “the reductionist school” assumes that decisions should be rational and that deviations from a purely rational approach are due to biases or errors. The second approach, “the pluralist school” argues that decision makers are rational but strongly influenced by personal and political interests which can be in conflict with the interests of the project. Here deviations from a purely rational approach are due to intra-group conflicts resulting in opportunistic behavior, bargaining, and conflicts. [5] The author argues that most of the AACE audience falls in the reductionist school, but that a pluralist approach must be understood and considered to improve outcomes. Moreover, decision makers such as gatekeepers need to identify and appreciate biases and political interests much better. This includes understanding systemic biases.

The literature, summarized by Stingle, Geraldi [5], identify three key ways biases manifest themselves in project decision making.

- Escalation of commitment: Projects continue despite clear warnings of failure. Optimism bias (the over estimation of positive outcomes), illusion of control (perceived control over project risks lead to downplaying these risks), group think (or sunk cost bias) and anchoring. These all contribute to this impact.

- Overoptimistic initial plans and forecasts: Planning fallacy, optimism bias, as well as strategic misrepresentations where individuals push pet projects. These are each contributing factors. [6]

- Negotiations: “A failure to balance interests, or the adoption of a strongly self-interested strategy in negotiations can lead to sub-optimal negotiations” [5] and therefore decisions. This becomes even more important in the context of stakeholders. As project decisions are made, negotiations made in bad faith might result in a stakeholder’s ire later in the project and thus affect project success.

Behavioral decision making has been well documented. For example, Parth [7] lists 5 major flaws that cause errors in decision making:

- Errors in logic

- False assumptions

- Unreliable memories

- Mistaking the symptom for the problem

- Biases

Mitigation measures from Parth [7] include:

- Self-feedback

- Critically questioning the biases of those that provide information

- Document experiences

- Critically thinking about reality

Mitigation involves awareness of biases and understanding of our own personal biases.

Building on this knowledge, this article proposes three improvements to gate keeping decisions:

- Debias the gatekeepers as much as possible.

- Improve communication among gatekeepers and between the gatekeepers and the project team.

- Promote intellectual honesty across all decision makers and providers of information.

Each of these will be discussed in detail in the context of the case studies that follows.

Stakeholders

AACE International defines stakeholders as “Decision makers, people or organizations that can affect or be affected by a decision” [8]. Dalcler [9] informally defines a stakeholder as “anyone affected, or potentially affected, by your work.” Bahadorestani et al [10] defines it as “individuals, groups or organization that have a stock or interest in project activities or outputs.” Recently, the Business Roundtable [25] revised its statement on the purpose of a corporation moving the emphasis from satisfying shareholders to that of satisfying stakeholders, which are described as customers, employees, suppliers, communities, and shareholders.

Embedded in these broad definitions is the notion that project success includes stakeholder criteria. Recent notions include the stakeholder as decision makers as opposed to creators or targets of value [11]. Thus, key project decisions such as project selection, allocation of resources, development of risk management strategy, managing contracts and the determination of the rights and responsibility of project participants all need to include key stakeholders. Nguyen [13] explicitly makes project success a function of stakeholder management and needs are always considered to be a critical success factor.

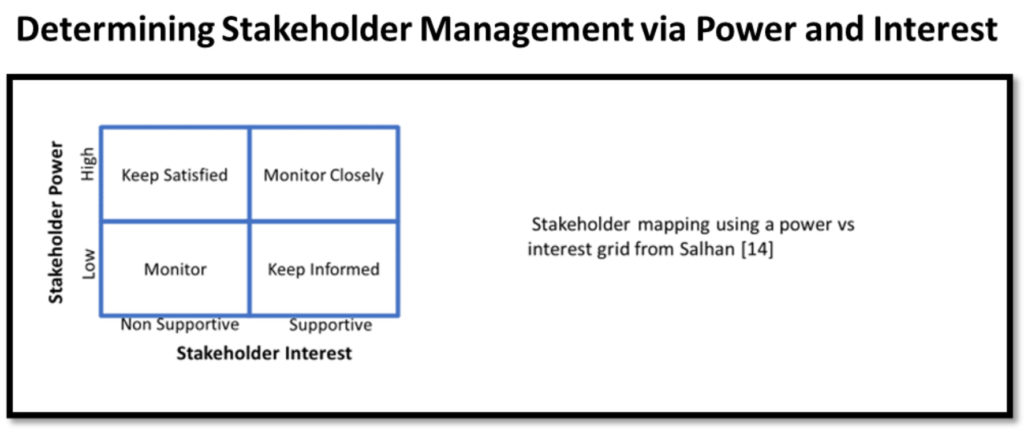

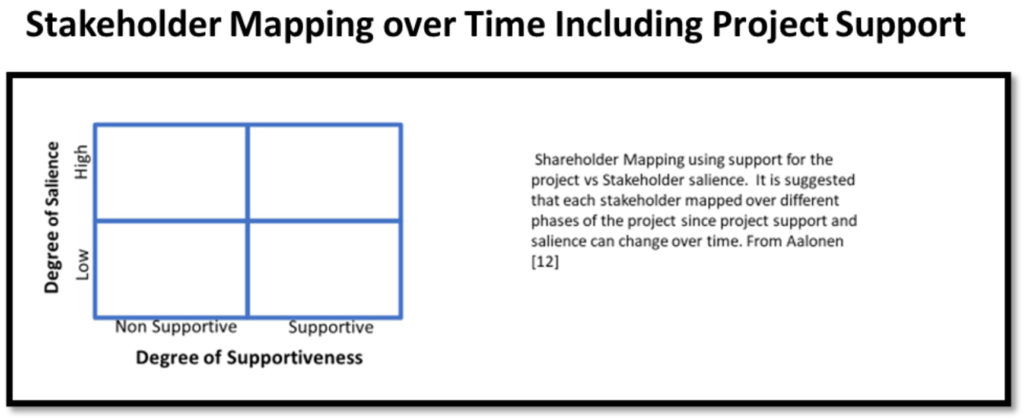

There are many ways to characterize stakeholders, but most focus on salience (the degree to which managers give priority to competing stakeholder claims [12]). Salience typically includes an assessment of stakeholder power, interests, attitudes [13] or more power, legitimacy, and urgency. [12] Aaltone promotes mapping stakeholders over time, across different project phases. Most project literature [22],[23] includes a stakeholder management section which typically includes stakeholder analysis, engagement, influence, and management strategies (such as inform, involve, proactively influence, collaborate, monitor, ignore, compromise, avoid or dismiss) [13]. Salhan [14] supports a power vs interest grid with strategies directly aligned with each 2 x 2 grid. Figure 8a and 8b shows some examples of stakeholder mapping to determine stakeholder salience and therefore which strategies to deploy. Figure 8a indicates that stakeholder salience is a function of stakeholder interest and power. Figure 8b indicates that once salience is determined, stakeholder’s can be further characterized by their level of project support. Further, stakeholder mapping should be done at various phases of the project since both salience and support can change over time. Smyth et al [15] explicitly states the natural conclusion of the above: that project managers need to consider more than just the iron triangle (cost, schedule, quality) and include stakeholder outcomes resulting from the downstream political, economic, and temporal risks of the asset created by the project.

Figure 8a–Determining Stakeholder Management via Power and Interest

Figure 8b–Stakeholder Mapping over Time Including Project Support

Stakeholders vary from project to project. Even in the simplistic case where a single company is executing a seemingly benign project to create a new asset, external stakeholders might include existing landowners, neighbors and the greater community, regulators (local, regional, state, federal – in the US) and utility suppliers (such as power companies, natural gas companies, water, and sewer authorities) as shown on Figure 7. Internal stakeholders will include the accountable person leading the project (ex: senior member of engineering organization), subcontractors, suppliers, treasury department, legal department, purchasing and real estate departments, operations department, and the business for which the asset is to be deployed. When projects get more complicated, the execution of the project starts to involve many other entities such as strategic partners, engineering contractors and their employees, construction subcontractors, FEED contractors, labor unions or groups, community activists, banks, owners, and public relations firms. And the most complicated projects have large roles for governmental entities (including ownership), multiple engineering and construction firms, project manager contractors, and many consultants (i.e., teams of lawyers, environmental and permitting consultants).

The key for the project manager is to understand which of these stakeholders is also a gatekeeper. This will change as the project progresses of course – each stage gate requires different interests. The focus of the rest of this article will be on the project authorization stage gate since this is typically the most important gate of project execution.

Some [16] have advocated that there are two approaches to stakeholder management:

- Management OF stakeholders. That is, getting the necessary resources from stakeholders.

- Managing FOR stakeholders. That is, stakeholders have a right and legitimate need for attention.

Depending on the project situation (small or large, simple, or complex, public or private) and specific stakeholders (salient or not, independent or interrelated stakeholders), each project needs to determine which of these two approaches to take.

Note figures 5 -7 reflect both internal and external stakeholders, regardless of an owner’s or contractor’s perspective. One question is which stakeholders will influence or should influence the decisions to be made by the gatekeepers. Another question is in which situations the project team should manage the stakeholders and when should the project be managed FOR the stakeholders. For example, in figure 7, the local community is shown as an exterior stakeholder. If the project is a public works project, the local community should influence the gatekeepers (and in fact they may very well be a gatekeeper) and the project needs to manage FOR the needs of the community. Cohesiveness, reasonableness, and supportiveness of the community will greatly determine the strategy to be deployed by the project team. But recognizing the local community as a stakeholder and managing them accordingly will greatly help the gatekeeping process and therefore the project.

Case Studies

To better understand the relationship between gatekeepers, stakeholders and decision making, two case study examples are provided – a simple project and a slightly more complex one. Truly complex projects, such as mega projects involving public entities will of course have much more complex issues. However, by focusing on two relatively simple projects, the essential issues become apparent and can be applied to more complex projects. The cases will illustrate the application of the three recommendations for improving decision making introduced earlier in this article.

Case Study 1: Simple Project

Project background

This project will be developed, financed, constructed, owned, and operated by the same company, primarily using its own resources. The asset will be located in an industrially zoned section of a US city. The locality is excited by the prospect of new jobs and increased tax revenues. There’s a primary customer for the asset’s production and that customer is expected to sign a long-term contract for the primary products. The customer is a long-time employer of the locality.

Gatekeepers

The gatekeepers at time of project approval (sometimes called project sanction or authorization) are:

- The business lead who will have profit and loss (P&L) responsibility for the asset.

- The engineering lead who has accountability for the cost, schedule, and quality performance of the asset creating project.

- Various corporate interests such as the lawyers (accountable for contracts and compliance), corporate real estate (responsible for land acquisition), finance (accountable for providing funding for the project), human resources (accountable for providing suitable resources), corporate purchasing groups (accountable for obtaining contracts for utilities and raw materials).

Note that these are all internal stakeholders. In this case the external stakeholders are determined to have low salience. Even though the project will affect neighbors (perhaps with noise) and require regulatory approval (say for emissions), the project approval stage holds the accountable internal stakeholders as the key decision makers or gatekeepers.

Decision-making

The project manager’s role in the project approval step varies from company to company but their signature is generally required on the approval documents. This signifies their accountability for cost, schedule, and quality requirements. They also need to clearly communicate project risks to the other gatekeepers. This is the most important job of the project manager during project approval – to provide the gatekeepers with a thorough and honest discussion of risks. John Hollman’s book [17] on risk quantification provides many excellent examples and techniques. But gatekeeping meetings must translate project risks for nontechnical stakeholders and must be done in the context they are familiar. Some methods toward that end are the front-end loading index (IPA) or project definition rating index score (CII). The discussions generated by these methods are typically more important than the absolute value of the score.

Note that in this simple case, the project stakeholders and gatekeepers are the same. That’s because in such a simple project, the external stakeholders are in a subservient role; even though they have a clear stake in the outcome of the decision (to approve the project) they have no voice in the decision. Thus, this is an example of management OF stakeholders.

Improvement of decision-making

Improvement of decision-making in this example relies on the following key elements:

- Debias: there’s a natural tendency toward optimism bias, biases in probability estimation, political bias, renumeration system bias and many others. [24] Other biases such as anchoring, cognitive inertia, confirmation bias, planning fallacy and other well-known biases [7] also come into play. Even in a simple example, human errors can easily slip into key decisions [20]. By simply being aware these biases exist, decision making can improve. In this simple project example, it is likely the gatekeepers are in their roles routinely and therefore have prior relationships. Depending on group dynamics, one effective method to debias is for a checks and balances approach where individuals can “call each other out” when exhibiting biases. Some examples:

a. The business lead might have optimism bias and challenge the schedule proposed by the project manager. The project manager should work to expose the bias based on facts, past history, what if analyses and logic.

b. The project manager might be biased by a previous project and be anchored in costs, risk or schedule assumptions that are not necessarily appropriate for the specific project. Reminding the project manager of other project performances and/or the specifics of the referenced project needs to be highlighted.

c. A stakeholder such as the end use customer might have a political bias and pressure the business sponsor that the proposed contract pricing should exclude needed environmental controls or actions. Exposing that bias by highlighting regulatory risks and realities is needed. - Communication skills: too many times, decision makers are not good listeners. If a gatekeeper is not listening properly to stakeholders, key points might be missed. Of course, the speaker needs to be clear, concise and have facts available to support their case. Examples:

a. A discussion on permit or land acquisition risks and contingency plans: Here the project might need an alternative site resulting in significant scope change later. But if this is poorly communicated at the project approval gate meeting (either poorly portrayed or not properly heard), future surprises might be in store.b. Risks associated with the ability to obtain critical raw materials at a given price: This might result in changes to the product portfolio that the project needs to produce. And in turn, this could result in a scope change or a change to the sales forecasts.

c. The project manager’s risk discussion regarding construction productivity risks associated with a very busy environment: If gatekeepers don’t understand the manifestation of those risks might result in significant cost or schedule overruns, an incorrect decision to approve the project might be made. - Intellectual honesty: Too often, a gatekeeper has a preconceived notion and refuses to acknowledge key points being made. This might be because the gatekeeper is not interested in or does not respect information provided (or the individual providing the information). Earlier in example 2c, regarding construction productivity risk, the business leader may have been told by a colleague at another company not to worry about construction productivity because the other projects proposed (that is driving the forecasted very busy environment) will likely not happen. The project manager might provide sufficient proof to the contrary but if the gatekeeper is not intellectually honest about the input, they are putting the project at risk. Part of intellectual honesty is integrity; the author acknowledges that it’s very hard to counter individuals that don’t have integrity. But many people with integrity are not intellectually honest for other reasons such as: it’s hard work or takes too much time, aren’t intellectually curious, don’t want to look foolish (or admit that previous beliefs were foolish), biases and a lack of humility. Establishing norms which promote and incentivize intellectual honesty is important – both at an organizational level and a project level. [26]

These three suggestions – debiasing, improved communication skills and ensuring intellectual honesty are typically intertwined. They are presented separately here only for illustration purposes. In practice, all three are necessary to improve the decision-making process.

Case Study 2: A Slightly More Complex Project

Project background

While a mega public project would provide a starker contrast, a project that is not so complex makes a clearer illustration of the intended point. For this case, it is assumed that the project will be developed, constructed, owned, and operated by the same company using its own resources along with major engineering contractors but financed by others. The asset will be located in highly visible part of a US city on the land of the customer. While the locality is excited by the prospect of new jobs and increased tax revenues there’s likely local opposition from environmental groups. There is a primary customer for the asset’s production and that customer is expected to sign a long-term contract for the primary products. The customer is a long-time employer of the locality however has had environmental issues in the past. The project needs significant regulatory approvals to proceed, and that approval is not at all certain.

Gatekeepers

The gatekeepers at time of project approval are similar to the above simple case. However, a decision board (or project steering committee) of senior corporate executives might be appointed as a formal gatekeeping entity, especially if the capital project size is large or it is deemed a complex project. Plus, the project must now include regulators as a salient stakeholder. The project sponsor may decide to take the risk and approve the project prior to regulatory approval. But a denial of project permits would in effect shut down the project and therefore it is essentially a gatekeeper as well.

External gatekeepers now become important during project approval processes. The power and urgency of the regulator suggests that that the project needs to pay much more attention here. Thus, the political process (community and government relations and lobbying), public outreach efforts and closely working with the local company will be key. Each of these entities might be considered de-facto gatekeepers as well. The decision might be to treat manage the stakeholders rather than execute the project FOR the stakeholders. However, management of the stakeholders might be much more nuanced and balanced than in case study 1.

Decision-making

In addition to all the factors discussed above, other issues start to come into play with complexity. Many companies have standard risk forms and processes which help put a specific project risk in perspective. Regardless, the project manager must ensure the documents properly communicate these risks in the context of their cost, schedule, and quality numbers. Flyvbjerg [6,18] has pointed out that through either omission, political sensitivity or outright lies (what he refers to as strategic misrepresentation), decision makers may or may not be thoroughly honest in these discussions. This is especially true with projects involving public entities and by extension perhaps public regulators. This applies not just in project risk discussion but in contract terms, sales forecasts and asset input pricing, quality, and availability.

As previously discussed, there’s also a planning fallacy argument that states that organizations underestimate costs and overestimate benefits. This presumes either a nefarious element or systemic bias. While this has been debated in the academic community [19], it’s not difficult to see the planning fallacy at work. Even in private business, decision makers have biases that might manifest in lies or strategic representation. For example, a business sponsor might be promoted upon expansion of a business line based on the asset creation process. That individual might not be in position 3–4 years later when the asset comes on stream, or 6–10 years later when profitability can be determined. Therefore, they might feel less accountable for their actions and influenced to promote the project by down-playing risks or overstating sales projections. In this example, the decision to approve the project despite regulator concerns might be examples of over optimism.

Improvement of decision making relies on similar elements as discussed earlier:

- Debias: Reference class estimating has been suggested as one mechanism to debias decisions. Reference class estimating involves having independent eyes review the estimate to provide an outside view. The author’s experience in private industry is that in the estimating space, reconciliation to other data points (prior projects, previously approved estimates, or even benchmarked data) provides a much better methodology. Most projects are sufficiently complex that an outside view will simply miss nuances of the process, scope or estimate assumptions. Further in the reality of competitive bids, projects naturally need to be part of a continuous improvement process. Therefore, prior projects or an outside view might miss the fact that value engineering has been done to legitimately reduce costs or schedule relative to the referenced projects or estimates.

- Communication skills: On complex projects, where stakeholders might be inter- dependent, communication skills go beyond what was described in the simple project example. A member of the project team might be appointed with the sole task of stakeholder management, for example, and/or there will be a much more active role for corporate communications’ involvement, media relations and proactive messaging. Outreach sessions might be needed to proactively listen to the stakeholders prior to a gate keeping meeting. Further, higher level meetings with the regulatory agencies might be wise prior to an approval meeting to understand the level of support that is there. In the case of an air permit for example, gatekeepers should meet with the permitting agency, consulting firm, as well as existing customers to understand mitigation, technology and permitting strategies. This is an example of a pro-active communication on the part of the gatekeepers.

- Intellectual honesty: For more complicated projects it is more difficult since each stakeholder has their own interests at heart. Though the principles discussed under case study 1 still apply. Politics will be involved and therefore value judgements of different gatekeepers and stakeholders will be different. Of course, not all stakeholders have the same outcomes in mind. The ability of project team members to appeal to logic, consistency, precedent (other projects) as well as other decision makers can help draw out the intellectual honesty of the individual. Other influence techniques such as appealing to the individual’s mentor or other respected person or even their superior may also be needed. This requires relationship building between and among the gatekeepers and salient stakeholders.

Alignment

This all speaks to the issue of alignment. The Construction Industry Institute (CII) publishes best practices and one of the most important is alignment. CII defines alignment as “the condition where appropriate project participants are working within acceptable tolerance to develop and meet a uniformly defined and understood set of project objectives.” While CII work is focused within the project, many of their recommendations apply to stakeholders: Team building and team alignment, on boarding members and stakeholders, consideration of cultural differences and constraints of stakeholders, ensuring continuity of key team members and development a mechanism to check on stakeholder alignment throughout the project life cycle. [21]

Project managers typically consider their teams consisting of engineering, procurement, construction, and commissioning team members. But by broadening the view team to include not only the key project team members, but salient stakeholders and gatekeepers, alignment starts looking differently. Ensuring alignment of both internal and external stakeholders is a key to success. When stakeholders are aligned, gatekeeping will be a much easier venture. The three improvements discussed above: debiasing, improved communication skills and intellectual honesty builds alignment as do the CII recommended practices listed above.

Impact of Misalignment

When the project authorization gatekeepers are misaligned with stakeholders, ill-defined and ill-prepared projects make their way through the process resulting in late changes and poor project results. This can happen when looking at even the simple project presented above.

The business lead is a key stakeholder but has goals which are typically not aligned with the project team responsible for execution. For example, the costs of going through the first three stages of project development are typically born by that business unit’s P&L if the project is ultimately not approved. If approved, the costs will be capitalized as an asset on the corporation’s books and therefore will not appear on the P&L. Thus, the business lead has significant incentive to limit project development and definition costs. The result of course is a potential for projects to lack proper definition. Of course, the business lead has a strong incentive for the project to succeed since both their customer and the long-term business P&L depend on it.

This contrasts from the execution team’s perspective which is to deliver on cost, schedule, and quality requirements. Their incentive is therefore to spend more time and money on project development so as to improve project definition, per project best practices. This is a natural tension that plays out all the time and typically results in a compromise of project development costs, scope, and schedule. It will be up to the execution team to properly communicate risks associated with any shortfalls of project development.

Regulators such as an air permit agency have very different perspectives. They will be interested in compliance, public input, and the project’s response to their questions. At project approval stage, it is unlikely for a large project to have their permits approved, especially since downstream engineering and design are required to even make permit application. However, gatekeepers need to be aware of the risk associated with regulatory approval and therefore need to consider the regulatory agency’s input. They can’t simply “manage” this stakeholder away. Gatekeepers may rely on an outside environmental consulting agency to provide an independent assessment of risk.

On more complex projects, the project steering team may decide, for example, to enlist a community relations and lobbying effort. Their feedback may suggest that the project is not ready to be approved because of significant resistance from either political agencies or the public at large. This may put them at odds with the business lead.

Table 1 summarizes the various gatekeepers for these simplistic cases:

|

Gatekeeper/Stakeholder |

Motivations |

|

Business Lead |

|

|

Engineering Lead |

|

|

Regulatory agency |

|

Table 1 — Summary of Various Gatekeepers for Simplistic Cases

Each gatekeeper has competing motivations and thus it’s easy to see the potential for misalignment. The business case might be based on getting to market quickly and at a certain budget. However, the engineered solution might take much longer, and cost more than originally anticipated due to either regulatory compliance or other unforeseen risk.

The issue of misalignment between stakeholders, gatekeepers and the project team can get more complicated very quickly. Figures 5-7 depicts even more stakeholders with even more varied motivations, each of which are potentials for misalignment. Furthermore, Figure 7 depicts the interaction between the external environment, the owner, the project, the EPC contractor, and the EPC’s sub-contractors. Between each of these layers, there exists stakeholders with various objectives and biases, communication challenges and opportunities for intellectual dishonesty. Both the external environment (with many stakeholders) and internal project environment (with many layers of responsibility) present opportunities for misalignment within the context of gatekeeping. And although beyond the scope of this paper, there are even further opportunities for misalignment in looking at more tactical and operational decision points as well.

Conclusion

This article reviewed gatekeeping as a series of strategic decisions from an owner’s viewpoint, though the perspectives of various contractors were also considered. Behavioral aspects of decision making were reviewed with emphasis on understanding decision making biases. Stakeholders and stakeholder management was discussed, noting the difference between internal and external stakeholders, as well as stakeholder salience. Projects are a series of decisions (strategic, tactical, and operational) and, from the owner’s perspective, stage gates are the most important strategic decisions. By adding stakeholders, these most important of decisions quickly become complex and subject to misalignment.

The article presented two case studies, both relatively simple projects relative to many mega projects. These simple cases demonstrate how stakeholders can be easily misaligned with gatekeepers. For the owner, no other decision is as important as project approval. The case studies suggest that even in simplistic projects, these decisions can be very complex. The same of course, holds for all the other decisions the owner, the project team, the EPC contractor, and individuals make. While it is easy to see the impact of poor decisions around project authorization, the same applies to any number of project level decisions and gates.

Project outcomes will be better aligned with the business case by improving our understanding of the decision-making process at key stage gates. Although the paper looked at rather simple projects, the potential for misalignment is clearly evident. More complex projects will have significantly more tension between stakeholders and gatekeepers, but the same principles will apply.

The article presented ways to improve project decisions by addressing bias, communication skills and intellectual honesty. When applied to gatekeepers and especially at the project authorization stage, these techniques can greatly mitigate impacts of misalignment. A savvy project team should facilitate these techniques to improve project outcomes.

Since the root cause of project failure often is a misalignment between the engineered solution and the owner’s business case, it is important for project teams to understand sources of misalignment. The focus of this paper is to explore one such source which is that stakeholders and gatekeepers have different objectives. By understanding and applying methods of stakeholder management and decision making, gate keeping can avoid being a source of misalignment.

- Morris, P.W.G., 2013. Reconstructing Project Management. John Wiley and Sons, Sussex, UK

- Walkup and Ligon, “The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly of the Stage-Gate Project Management Process in the Oil and Gas Industry.”

- Cab Cabano, Stephen L., Paul G. Williams, and Robert C. Mathias. “The Owner’s Project Control Function,” 2011 AACE International Transactions OWN.503.

- L. Stephenson, Ed., Total Cost Management Framework: An Integrated Approach to Portfolio, Program and Project Management, 2nd ed., Morgantown, WV: AACE International, Latest revision, section 3.3.2.

- Stingl, Verena, and Joana Geraldi. “Errors, Lies and Misunderstandings: Systematic Review on Behavioural Decision Making in Projects.” International Journal of Project Management, 35, no. 2 (February 2017): 121–35.

- Flyvbjerg, Bent. “From Nobel Prize to Project Management: Getting Risks Right.” Project Management Journal, 37, no. 3 (August 2006): 5–15.

- Parth, Frank R. “Critical Decision Making for Project Planners and Controllers,” AACE International Transactions,2014, RISK.1504

- AACE International, Recommended Practice No. 10S-90, Cost Engineering Terminology, Morgantown, WV: AACE International, Latest revision.

- Dalcher, Darren. “In Whose Interest? Repositioning the Stakeholder Paradox,” PM World Journal (Issn:2330-4480) Vol IX, Issue IX, September 2020.

- Bahadorestani, Amir, Jan Terje Karlsen, and Nasser Motahari Farimani. “A Comprehensive Stakeholder-Typology Model Based on Salience Attributes in Construction Projects.” Journal of Construction Engineering and Management, 145, no. 9 (September 2019): 04019048.

- Derakhshan, Roya, Rodney Turner, and Mauro Mancini. “Project Governance and Stakeholders: A Literature Review.” International Journal of Project Management, 37, no. 1 (January 2019): 98–116.

- Aaltonen, Kirsi, Jaakko Kujala, Laura Havela, and Grant Savage. “Stakeholder Dynamics during the Project Front-End: The Case of Nuclear Waste Repository Projects.” Project Management Journal, 46, no. 6 (December 2015): 15–41.

- Nguyen, Tuan Son, Sherif Mohamed, and Kriengsak Panuwatwanich. “Stakeholder Management in Complex Project: Review of Contemporary Literature.” Journal of Engineering, Project, and Production Management, 8 (June 5, 2018).

- Salhan, Pranav. “A Study on Stakeholder Management of an Engineering Project.” International Journal of Engineering Research and V9, (June 5, 2020).

- Smyth, Hedley, Laurence Lecoeuvre, and Philippe Vaesken. “Co-Creation of Value and the Project Context: Towards Application on the Case of Hinkley Point C Nuclear Power Station.” International Journal of Project Management, 36, no. 1 (January 2018): 170–83.

- Eskerod, Pernille, Martina Huemann, and Grant Savage. “Project Stakeholder Management—Past and Present.” Project Management Journal, 46, no. 6 (December 2015): 6–14.

- Hollmann, John K. Project Risk Quantification. Probablistic publishing, Gainsesville, FL 2016

- Flyvbjerg, Bent, Massimo Garbuio, and Dan Lovallo. “Delusion and Deception in Large Infrastructure Projects: Two Models for Explaining and Preventing Executive Disaster.” California Management Review, 51, no. 2 (January 2009): 170–94.

- Ika, Lavagnon A. “Beneficial or Detrimental Ignorance: The Straw Man Fallacy of Flyvbjerg’s Test of Hirschman’s Hiding Hand.” World Development, 103 (March 2018): 369–82.

- Pinto, Jeffrey K. “Lies, Damned Lies, and Project Plans: Recurring Human Errors That Can Ruin the Project Planning Process.” Business Horizons, 56, no. 5 (September 2013): 643–53.

- https://www.construction-institute.org/resources/knowledgebase/best-practices/alignment

- Project Management Institute, ed. A Guide to the Project Management Body of Knowledge (PMBOK Guide). 2000 ed. Newtown Square, Penn., USA: Project Management Institute, 2000.

- Turner, J. Rodney, ed. Gower Handbook of Project Management, 4th ed. Aldershot, England; Burlington, VT: Gower, 2007.

- Williams, Terry, Hang Vo, Knut Samset, and Andrew Edkins. “The Front-End of Projects: A Systematic Literature Review and Structuring.” Production Planning & Control, 30, no. 14 (October 26, 2019): 1137–69.

- Business Roundtable. “Statement on the Purpose of a Corporation.” https://Opportunity.Businessroundtable.Org/Ourcommitment/, 2019.

- Samson, A. (Ed.)(2020). The Behavioral Economics Guide 2020 (with an Introduction by Colin Camerer). Retrieved from https://www.behavioraleconomics.com.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

David C. Wolfson is with Pathfinder, LLC, and can be contacted by sending email to:

dswolfson@yahoo.com

Rate this post

Click on a star to rate it!

Average rating 4.6 / 5. Vote count: 7

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.