Estimating As It Pertains to Risk Management

by Shoshanna Fraizinger, CCP

Abstract–The outputs of estimating are typically a primary input for business planning, cost and risk analysis, management decisions, and project cost and schedule control processes. All these aspects of corporate strategy and project planning are bounded, or guided by, an organization’s risk appetite.

Estimating is fundamental to the ‘Assess’ & ‘Treat’ steps of risk management, as defined in AACE’s Total Cost Management Framework (TCM) and Skills and Knowledge of Cost Engineering 6th Edition (S&K6). Estimator skill is required to determine the cost impact of the risk (assess), and the cost to implement the plan to address the risk (treat), respectively. The cost impact of the risk contributes to the amount of contingency required. However, there are several facets of strategic planning wherein the cost estimating process can introduce, assess, or mitigate risk.

This document addresses the topic of estimating as it pertains to risk and the various facets of project risk, which can be affected by the cost estimate and the methods by which the estimates are developed. This paper is aimed at the junior to intermediate cost engineering professional and provides a single source for AACE references on this subject. This article was first presented as EST.3429 at the 2020 AACE International virtual Conference and Expo.

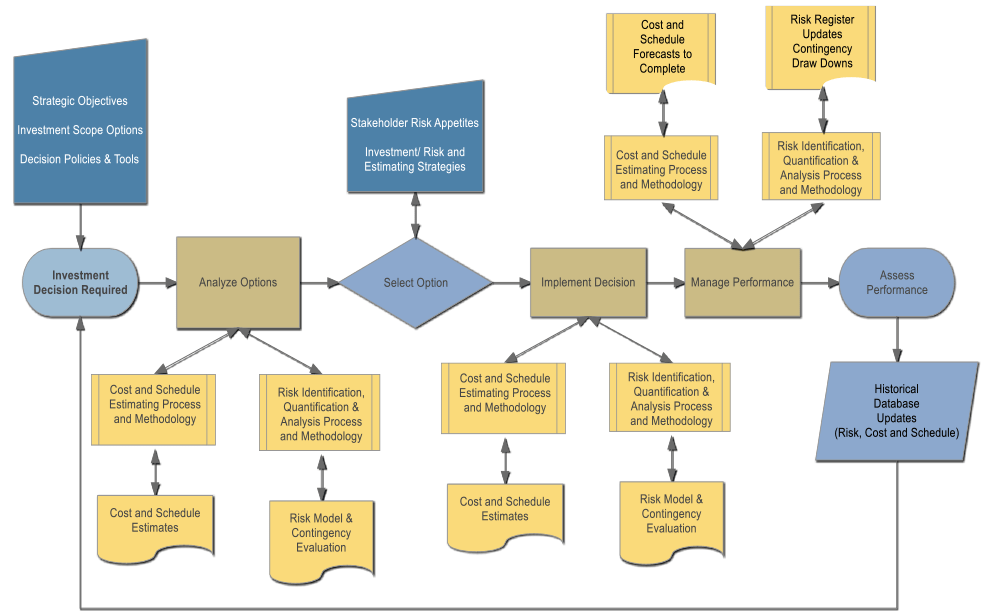

Corporate investment, which results in the continued successful operation that meets or exceeds, defined strategic goals and objectives, drives the need for portfolios, programs and projects.

Figure 1–Investment Planning, Decision, and Implementation Process Flow

This paper aims to provide a general overview and discussion of the cost estimating process, the risk management process, the various facets of the cost estimate process and outputs which pertain to risk at each interface point within the investment planning, decision and implementation process and provides general recommendations to the cost estimating practitioner concerning the minimization, or elimination, of those aspects of risk which are within their control to manage.

Discussion on the Cost Estimating Process

This calculation is ideally performed using:

- Applicable, quality (i.e. best available) input data as a basis for scope and factoring,

- Industry best practices and methodologies for development,

- Consistent processes for documentation, review and assessment; and,

- Reasonable judgement in ascertaining if the outputs are useable

The outputs of this calculation result in some range of probable values, from which a single number is often be selected for use. The users of this value have expectations of it being credible, and reliable, for the purposes of appraising the scope, and whether the thing being evaluated is worth pursuing (or continuing).

In AACE’s Total Cost Management Framework [1], cost estimating is defined as “the predictive process used to quantify, cost, and price the resources required by the scope of an investment option, activity, or project.” [2, p. 90]. The output of this process is the cost estimate itself, which is often described and documented in a basis of estimate document.

It is apparent when referring to figure 1 above that output of the estimating process, may be used for many purposes, including:

a) The determination and selection of the best investment option from several alternatives,

b) The economic feasibility of the selected option for decision making,

c) The establishment of the project budget once the decision to proceed has been made,

d) The proper application of the risk management process for the determination of contingency and reserves,

e) The management, reporting and control of the project against that budget once implementation is underway; and,

f) The provision of additional inputs to a corporate historical database, which provides the basis and benchmarking for future endeavors of similar requirements.

The Function of the Cost Estimator

AACE’s Recommended Practice 10S-90, Cost Engineering Terminology [3] defines cost estimator’s function as “COST ESTIMATOR (PROJECT) – Project cost estimators predict the cost of a project for a defined scope, to be completed at a defined location and point of time in the future. Cost estimators assist in the economic evaluation of potential projects by supporting the development of project budgets, project resource requirements, and value engineering. They also support project control by providing input to the cost control baseline. Estimators collect and analyze data on all of the factors that can affect project costs such as: materials, equipment, labor, location, duration of the project, and other project requirements. (November 2012)” [3, p. 35]. This is further elaborated in AACE’s Recommended Practice 101R-19, Roles and Responsibilities of a Project Cost Estimator. [4]

The value of the cost estimating process lies in its capacity to predict the final cost of a planned scope of work, with some measure of reasonable certainty; however, by its very nature, the cost estimate is a prediction and, therefore, uncertain. It is therefore vitally important that:

- The cost estimate is accurate, concerning each of the stakeholder’s end uses to limit the amount of uncertainty within the cost estimate and,

- That the estimator understands the concept of risk and the risk management process as well as the fundamentals of developing and documenting a cost estimate correctly.

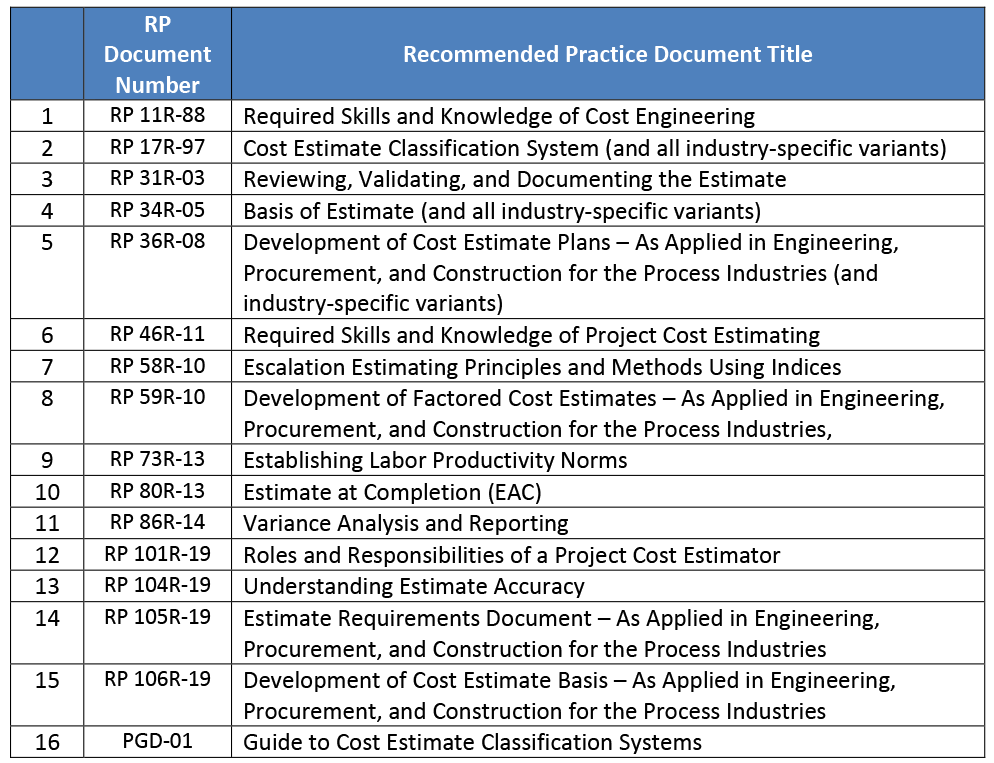

AACE has several recommended practices (see table 1), as well as professional practice guides, which describe in detail the industry best practices for cost estimating, including the requirements for the development, documentation, and classification of cost estimates to ensure a high degree of accuracy. The cost engineering practitioner is advised to consider the guidance provided in these documents when performing cost estimating process activities.

Table 1–List of AACE Recommended Practices (Cost Estimating Topics)

Discussion on the Risk Management Process

AACE’s Recommended Practice 10s-90, Cost Engineering Terminology [3], defines risk as:

(1) An ambiguous term that can mean any of the following: a) All uncertainty (threats + opportunities); or b) Undesirable outcomes (uncertainty = risks + opportunities); or c) The net impact or effect of uncertainty (threats – opportunities). The convention used should be clearly stated to avoid misunderstanding.

(2) Probability of an undesirable outcome.

(3) In total cost management, an uncertain event or condition that could affect a project objective or business goal.

See also: CONDITION (RISK CONDITION); EVENT; OPPORTUNITY; THREAT; UNCERTAINTY. (December 2011) “ [3, p. 102]

In reviewing this definition, it can be extrapolated that a cost estimate, due to its probable nature, can be a risk in and of itself to the project. If the cost prediction is wrong, there is certainly a higher probability of an undesirable outcome for the project.

What is Risk Management?

Risk management is the process by which an organization plans for, identifies, quantifies, analyzes, responds to, monitors, controls and reports risk within a strategic investment option (be it a project, program, portfolio).

AACE defines risk management in Skills and Knowledge 6th Edition (S&K6) [2] as: “the process of identifying risk factors (risk assessment), analyzing and quantifying the properties of those factors (risk analysis), treating the impact of the factors on planned asset or project performance and developing a risk management plan (risk treatment), and implementing the risk management plan (risk control)” which is a direct citation from the TCM Section 7.6.1. [2, p. 407].

The S&K 6 further elaborates that “the goal of risk management is to increase the probability that a planned asset or project outcome will occur without decreasing the value of the asset or project. Risk management presumes that deviations from plans may result in unintended results (positive or negative) that should be identified and managed” [2, p. 407]

From this definition, it can be seen that there is an expectation that the risk management process results in a variety of response alternatives being identified and which must then be assessed to evaluate whether they address the risk sufficiently such that established thresholds for the project (be they cost, schedule, quality, safety or technical performance) are not exceeded.

In aide of these risk management process activities, the cost estimator is expected to contribute to the process by providing the following inputs directly to crucial risk management process steps:

- The characterization and quantification of the cost impact of the risk element(s) in the project, which are usually captured in the project risk register.

- The characterization and quantification of the “cost to implement” for the various response alternatives so the best solution for addressing the risk element can be selected and incorporated into the base estimate for the project

- Evaluation and quantification of residual contingency requirements needed to achieve the necessary estimate classification level.

The Nature of Estimates and their Relationship to Risk

Project cost and schedule estimates are predictions based on empirical data. Because they are predictions or put another way “very-well educated guesses,” it means these estimates are inherently uncertain, and there are a variety of factors which can contribute to that uncertainty, which include the following:

- The level of maturity and definition may be very low because the project is still in the earliest stages of planning and many elements of scope, contracting and execution strategy may as yet, be undefined (or poorly defined)

- The organization’s estimating processes, procedures and tools may be rudimentary, poorly documented or exercised in an ad hoc manner leading to inconsistencies in both historical information for estimating input reference as well as a loose definition of estimating development practices.

- The strategic planning assumptions forming the basis of the estimate were not necessarily validated with, or accepted by, all estimate stakeholders

- The organizational objectives for the project were not well communicated to the estimator and, therefore, not documented appropriately in the estimate development files.

- Factors external to the estimating process, which might have influence over the cost in the estimate were not readily identified and addressed in the estimate. These could include such things as the cost of raw materials, labor rate changes, unique contract terms and conditions, etc.

- The organization operates in a siloed environment and does not necessarily integrate the estimator adequately in the risk identification and quantification processes leading to potential inaccuracies in the ranging information and risk modelling.

The value of applying the risk management process to the activities defined in the investment decision-making process (including the cost estimating process), lies in the fact that that it is a structured process to anticipating and assessing the various ways an investment endeavor can be affected by uncertainty to inform effective decision making that can reduce that uncertainty and thereby improve the success of the endeavor.

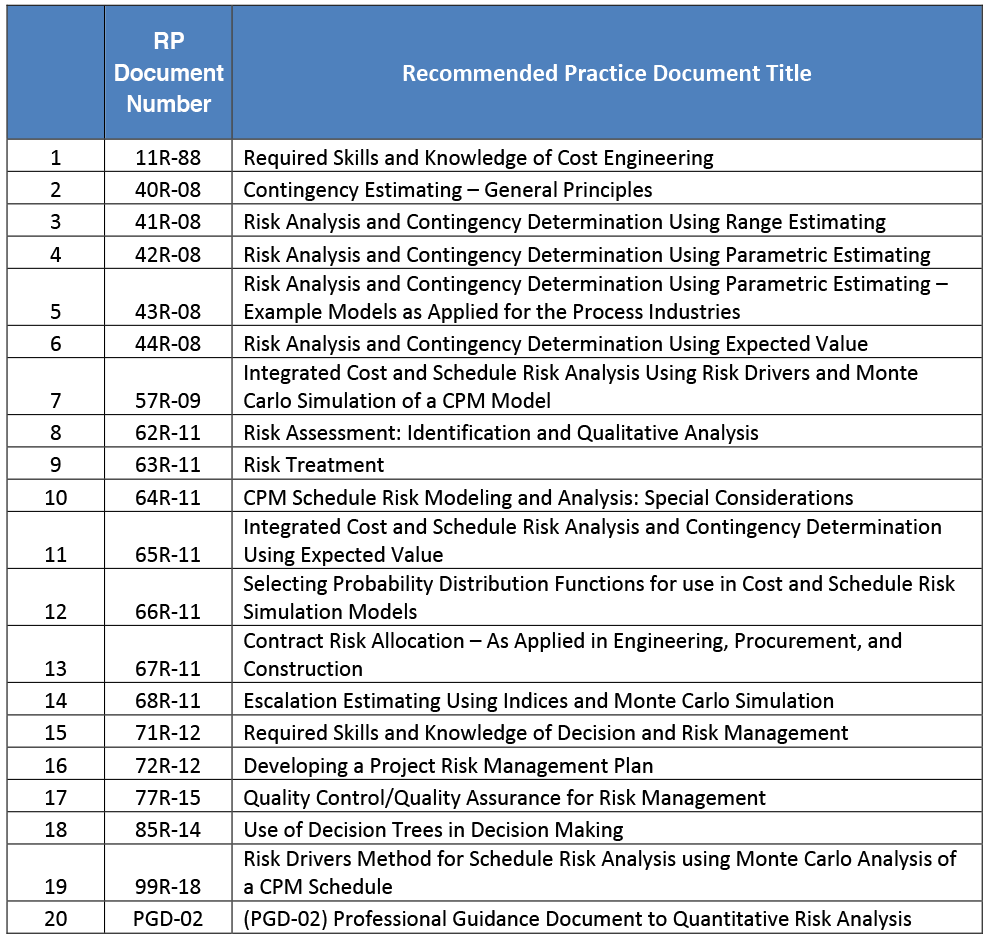

AACE has several recommended practices (see table 2), as well as a professional practice guide, which describe in detail the industry best practices for risk management, including the requirements for the planning, identification, assessment, treatment of risk as well as development and use of risk models for analysis. The cost engineering practitioner is advised to consider the guidance provided in these documents when supporting the risk management process and identifying required contingency within the estimate.

Table 2–List of AACE Recommended Practices (Cost Estimating Topics)

The Many Facets of Risk an Estimator Needs to Consider within the Estimating Process

As discussed above, there are many aspects of cost estimating, which pertain to the subject of risk, and the process of risk management on a project. There are also several ways in which the cost estimating process can affect or even introduce risk to a project. The cost estimator should be aware of these considerations when preforming their tasks to ensure they effectively capture and document the technical risks associated with executing scope in the project, as well as trying to minimize the potential for introducing new risks to the project through their actions.

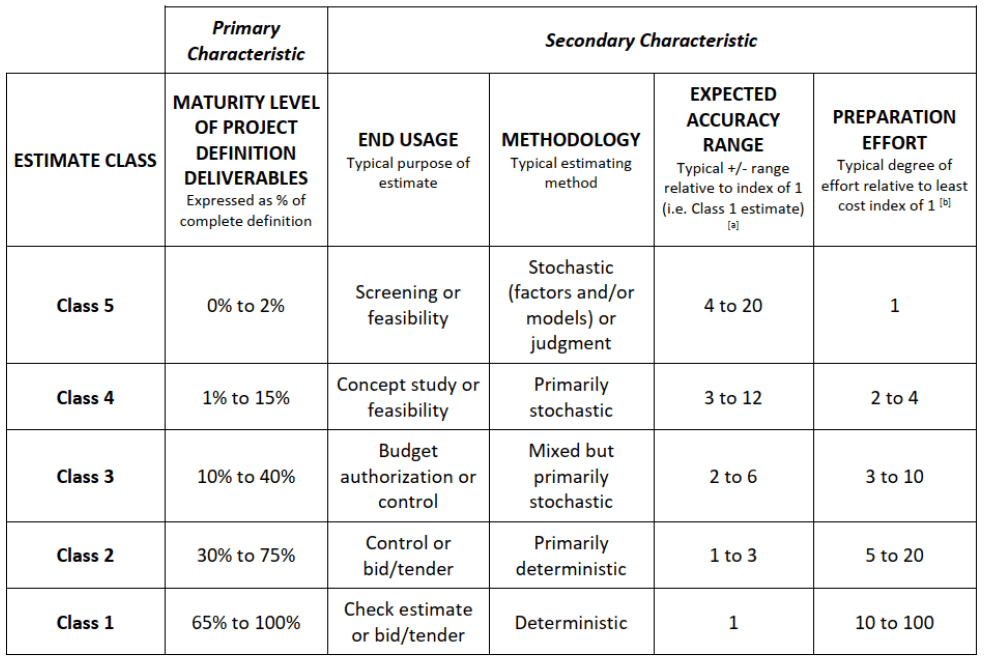

Recall from AACE RP 17R-97, Cost Estimate Classification System [5], that “the Cost Estimate Classification System maps the phases and stages of project cost estimating together with a generic project scope definition maturity and quality matrix” [5, p. 1] and helps guide the estimator for the correlation of required scope maturity, to the potential estimate categorization and end-use, as well the required methodologies, accuracies and effort necessary to achieve that categorization. This correlative mapping guidance is summarized in figure 2.

Figure 2–Generic Cost Estimate Classification Matrix Provided as Table 1 in RP 17R-97 [5, p. 5]

Many of the characteristics identified in figure 2 can be subjective, depending on the standards and processes employed by the organization developing the estimate, which can introduce the potential for uncertainty that an estimate as presented truly represents the characterizations expected by the RP. It becomes the responsibility of the estimator to then employ the guidance provided in RP 31-03, Reviewing, Validating, and Documenting the Estimate [6] to ensure the cost estimating process has been followed judiciously and with prudence.

Further, if the assessment of the estimate characteristics are not appropriately aligned (vis a vis the applied definition of the characteristic) to the expected, or required, characterization of the estimate class designation as defined by the guidance in RP 17R-97, this also creates the potential for uncertainty as the applied ranging values may be incorrect and inadequate for proper contingency evaluation. An excellent AACE technical paper by J. Hollman, R. Bali, C Germain, M. Guevremont and K. Kai-man entitled “Variability in Accuracy Ranges: A Case Study in the Canadian Hydropower Industry” [7], which discusses this issue and can be found in the AACE virtual library for further reference. While the case study centers on a particular industry, the lessons learned from the example can be applied elsewhere.

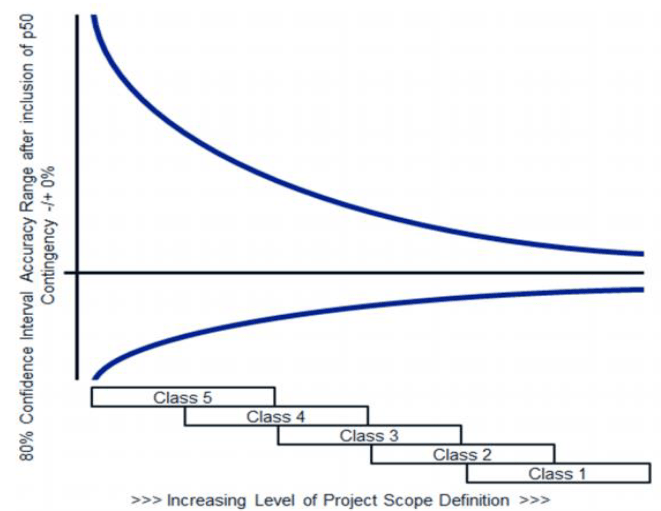

Recall from RP 17R-97, Cost Estimate Classification [5], that “the estimate accuracy range is an indication of the degree to which the final cost outcome for a given project will vary from the estimated cost. Accuracy is traditionally expressed as a +/- percentage range around the point estimate after the application of contingency, with a stated level of confidence that the actual cost outcome would fall withing this range” [5, p. 5]. From this it can be understood that, within AACE, the industry best practice with respect to communicating about the base estimate is more properly conducted using a “range of ranges” rather than one particular “point value”. AACE Recommended Practice 18R-97, Cost Estimate Classification System -As Applied in Engineering, Procurement, and Construction for the Process Industries [8] (recently updated in March of 2019), provides a graphical representation of the variability in accuracy ranges as shown in figure 3 below.

Figure 3–Illustration of the Variability in Accuracy Ranges for Process Industry Estimates as provided in RP 18R-97 [8, p. 5]

Risk Management Considerations within the Estimating Process

Some of the risk management considerations which must be evaluated or addressed in the cost estimating process by the estimator are noted below. The items identified by no means represent a comprehensive list, as there are industry-specific nuances which may also need to be considered, however, these are presented as a few general guidelines for review:

-

- The Risk appetite of the Organization – As per Chapter 9, Cost Estimating of the S&K6 [2], “ The capital cost of a proposed project is one of the key determinants in evaluating the financial viability and business case of the project” [2, p. 90]. This financial viability evaluation is always made in relation to the risk appetite of the organization. An organization willing to “take a risk” on a project may dictate the development of an aggressive (low-cost value) estimate, and conversely, the organization which does not have much free capital to lose in pursuit of an endeavor may choose to move forward with a conservative (higher cost value) estimate. If the estimator does not understand the risk appetite of the organization, i.e. how aggressive or conservative they wish to be in pursuit of the project, they may run the risk of developing or documenting the estimate inappropriately. As an example, an organization that leans toward an aggressive estimate may want very few allowances added to their estimates; they may want to adjust the skew applied in the risk modelling.

- The Risks “Internal to the Estimating Process” – The process and diligence by which the estimator has quantified base costs and pricing, the logic and planning and duration basis and assumptions, applied allowances etc. can all introduce uncertainty and affect risk in the project. If an estimator is not aware, for example, that; the organization has changed elements of the estimating standards to be applied, a template has changed concerning resources rates or applicable overhead percentages, a norms reference has been used but it hasn’t appropriately aligned into the estimating database with the correct location basis for the project – All of these can create error in the estimate, and that creates uncertainty that the estimate presents a correct base cost for the scope of the project.

- The Risks “External to the Estimating Process” – Projects, by their nature, can be moving targets as they are iterated through their lifecycle from initiation to closeout. The definition of scope and execution may completely shift from what was initially understood by the project team and communicated to the estimator. When this happens, it introduces uncertainty that the estimate as developed to that point remains valid going forward for the project. Examples can include situations where contractual constraints are applied such that project cost and schedule have dictated maximum allowable thresholds that must be maintained, or a primary stakeholder does not like the price in the estimate, leading to a complete revamp of scope through a value engineering study late in the project lifecycle. The skilled estimator should understand that these situations can happen on a project and seeks to maintain the highest levels of communication with stakeholders so they can be in the best position to address these constraints and changes.

- Self-Created Risks – The quality and level of maturity of the inputs, the bias of reviewers, and other factors influencing the cost estimating process all contribute to the relative inaccuracy of the base estimate, regardless of how diligently the estimator has applied standards and processes. An estimator must be cognizant of these aspects of the inputs to the cost estimating deliverable and ensure they do not “over-present” the characterization of estimate class; this would result in what is being termed as a “self-created risk.” If the project has provided estimating inputs that can at best characterizes the project as 5% complete, they should not accept a request to develop an estimate required for budget authorization or control; however it is all too often the case that estimators are provided with inputs with a much lower level of definition than the requested end-use for the estimate.

- The Risk Quantification Step of the Risk Management Process Itself – In this context, the reference is to the action of providing input to the risk register line item costing and ranging of these items. The cost estimator is in the best position to understand which elements of uncertainty were addressed in the base estimate costs and ensure that the risk register accounts for the elements of uncertainty that were carried over from the base (i.e. not included as base cost). The base estimate, in conjunction with the risk register (line item and response plan) costs will form the complete foundation from which the project contingency range of values will be formulated through risk modelling and analysis.

- The Cost and Schedule Risk Modelling and Analysis Used to Develop Contingency Levels for the Project – Just as a skilled risk analyst will have some understanding of the cost estimating process, so too should the skilled cost estimator have an understanding of the risk modelling process and analysis methodologies. If the model and analysis do not account; for example, for all of the assumptions and exclusions applied in the development of the base estimate, or the overall strategy for the project, and contractual constraints, then the familiar adage “garbage in, garbage out” applies and this results in a new introduction of uncertainty concerning how appropriate the contingency values will be to maintain confidence in the project budget.

- The Budget Control and Performance Forecasting Used During the Management and Control Aspects of the Project – There are two aspects of the management and control process for a project that the estimator should be aware of when considering the estimate and associated risk management because the process of risk management does not stop once the budget has been authorized against the base estimate and work will be allowed to proceed.

The first aspect is the level of rigour applied by the project team to the management and control against the baseline. There are significant case studies that show projects having overrun their cost and schedule estimates, and very often, the general commentary as to why this occurs runs along the lines of “the estimator didn’t get it right.” Poor adherence to control and management processes will introduce uncertainty in the project’s ability to adhere to the original baseline. Ill-defined rules of credit, loose change management practices, and misaligned reporting intervals can all contribute to the scenario whereby the project actuals do not match the project estimate. The estimator should ensure they are engaged throughout the lifecycle of the management and reporting process to ensure that actual execution is progressing within the assumptions and scope limitations that define the base estimate.

The second aspect comes from the application of a well-defined change management process, which involves the assessment of the change impact (be it cost or schedule) which must then be calculated by the estimator and the baseline, and associated review, validation and documentation appropriately updated to reflect the new state of play for the project.

The quality, quantity and applicability, of the inputs that define our knowledge of some “thing” (be it a project, program or portfolio) all affect the accuracy and certainty of the outcomes of any process which relies on these inputs. This is most true for cost estimating and risk management processes. If the project scope, execution and estimating strategies, risks, etc. (inputs) for a project (the thing) are not defined or are poorly understood, the estimate (as the output of the cost estimating process) will also be poor. This creates uncertainty that the risk management process which follows, will produce reasonable results in evaluating and defining the required contingencies to enable project success against objectives.

There is also the matter of personal “bias” to consider. The bias of the user of any cost estimating and risk management process inputs will affect the way the inputs are used to create outputs, and the bias of the receiver of these process outputs will also affect how they interpret the results of the process. A skilled estimator will seek to understand and remove bias from their work and communicate about their estimates in such a way as to remove the bias of those who are estimate stakeholders.

The estimator should remember that the quantification of risk is relative to whatever has been developed as a base estimate (this is an observation that applies to both cost and schedule base estimates). It is also influenced by the base. If the base value is aggressive (very lean and without many allowances), the associated contingency required to achieve funding approval will be correspondingly higher to achieve the same level of confidence in the number provided. (This is assuming these values and confidence ranges are decided based on estimate classifications as per AACE RP 17R-97 and associated industry-specific variants). Therefore, the base should be as complete and well documented as possible so it can be understood and evaluated appropriately.

Conclusions

Estimating of risk items following industry best practices should be standard procedure for an organization’s project controls and project management functions.

Whether these estimates are developed using range estimating, conceptual or definitive estimating techniques (as dictated by the level of project definition available to the estimator), the resultant quantified risk dollar value will be as accurate as possible to either over-fund, or under-fund, the required project risk value (i.e. amount of contingency).

Ensuring a project has a valid, credible, and accurate amount of contingency available to address risk throughout the project lifecycle is a key element to ensuring a successful project outcome.

The collective AACE recommended practice [HQ8] guidance on cost estimating and risk management provides the fundamental direction to the estimator that summarizes to the following observations:

- To quantify risk as part of the risk management process, one needs a well-developed base estimate from which to assess the remaining risk in the project. Further, cost estimating input is needed for the expected costs associated with risk exposure, expected monetary values before and after mitigation, and the costs associated with any response plans.

- For the estimator to do this well, they first need to understand the risk appetite of the organization performing the project and the attendant estimating strategy.

In essence, the concept of cost estimating (as defined and used in AACE), includes the elements of risk quantification, and base estimates should always be considered the starting point to the iterative process of identifying, quantifying, assessing and managing risk.

When developing the base, an estimator must ensure the following to support the successful output of the cost estimating process for input to the risk management process:

- Reference data is relevant and correct

- Source has been scrubbed before use

- Project-specific factors have been applied consistently

- The outputs have been reviewed for quality and alignment against governance procedures

- The basis, assumptions, plan, strategy and development outputs have been well documented (i.e. in an accurate and fulsome manner).

When communicating about the base estimate, the estimator should be aware that because of the uncertainty within; the estimating inputs, the estimating process and the other elements as discussed earlier, the base estimate is best described as a range of contextualized values which should incorporate the risk elements and aspects of the projects.

1. H. L. Stephenson, Ed., Total Cost Management Framework: An Integrated Approach to Portfolio, Program and Project Management, 2nd ed., Morgantown, WV: AACE International, Latest Revision.

2. D. M. Hastak, Ed., Skills and Knowledge of Cost Engineering, 6th ed., Morgantown, WV: AACE International, 2015.

3. AACE International, Recommended Practice No. 10S-90, Cost Engineering Terminology, Morgantown, WV: AACE International, Latest revision.

4. AACE International, Recommended Practice 101R-19, Roles and Responsibilities of a Project Cost Estimator, Morgantown, WV: AACE International, Latest Revision.

5. AACE International, Recommended Practice No. 17R-97, Cost Estimate Classification System, Morgantown, WV: AACE International, Latest revision.

6. AACE International, Recommended Practice No. 31R-03, Reviewing, Validating, and Documenting the Estimate, Morgantown, WV: AACE International, Latest revision.

7. J. K. e. Hollman, RISK.1721 – Variability in Accuracy Ranges: A Case Study in the Canadian Hydropower Industry, Morgantown, WV: AACE International, 2014.

8. AACE International, Recommended Practice No. 18R-97, Cost Estimate Classification System – As Applied in Engineering, Procurement, and Construction for the Process Industries, Morgantown, WV: AACE International, Latest revision.

Rate this post

Click on a star to rate it!

Average rating 4.6 / 5. Vote count: 7

No votes so far! Be the first to rate this post.